Recently I was copied on an email sent from a well-known nonfiction author to other nonfiction writers. The author was wondering about how to deal with an editor who was suggesting the addition of lots of "extras" to the book she was writing. These extras could be videos linked to an e-book, sidebars or "fun facts," photographs and illustrations, graphs, charts, tables, and more.

Now those of us who teach may already be aware of the research that says that "extras" that distract readers attention from the main idea of a text do affect comprehension...and not in a good way. Kids may begin to believe that the interesting facts offered are, in fact, the main idea. After all, look how interesting they are! They must be important.

Here's what I think. When all the nonfiction features are working together in a supportive way, then that constitutes excellent nonfiction. Check out Locomotive, the best example I know of how nonfiction features support each other. That is, the

main idea, structure, style, integration of visual information, and

disciplinary thinking are mutually supportive. An excellent text doesn't need extraneous extras to amuse and excite readers. It's already engaging enough.

Don't get me wrong. I am not against extras. I am only against extras that distract readers and don't help them build understanding of the main idea of a book. And, I am finding it very encouraging that writers and teachers are coming to the same conclusion. That's probably because good writers don't need distracting extras because they write so well that their writing both informs and holds our interest.

So, I am thinking that when we look as "extras," we ought to ask: Does that feature support the main idea of the book or does it distract from its message? Such a simple question just might yield surprising answers.

Monday, December 23, 2013

Thursday, November 21, 2013

A Picture-Book Biographer Sets the Record Straight

I thoroughly enjoyed the AASL

meetings last week in Hartford. I went

to several author panels. It’s always

fun to put a face and voice to an author’s name, and to hear their thoughts

about the craft. Among the highlights

was a panel on picture book biography, skillfully moderated by Mary Ann. I was dazzled by how much effort goes into a

top-notch picture book biography, as shown in an anecdote that Matt Tavares related

about his research. He was working on Hank Aaron’s Dream, and had decided to

feature a well-known story about Ted Williams and Aaron. Here’s how Tavares tells it on his website (www.matttavares.com/hadmaking.html):

He was a 20-year-old minor leaguer, traveling

with the big-league Braves during spring training in 1954, playing the last few

innings of each game. Then on March 13, the Braves' starting left-fielder,

Bobby Thomson, broke his ankle during a spring training game. The very next

day, on March 14, the Braves played the Boston Red Sox in Sarasota, and Henry

Aaron was the new starting left-fielder for the Braves. He hit a home run that

day, and the sound of his bat hitting the ball was so spectacular that the great

Red Sox superstar Ted Williams came running out from the clubhouse to see who

had hit that ball.

It’s a terrific story, verified in Aaron’s autobiography and an article

by Williams. But when Tavares wanted the

illustration to include the line-up for the game, he tracked it down in digital

newspaper archives. That’s when the

whole story started to unravel: the date was wrong and Ted Williams was in a

hospital in Boston during that game.

Tavares’s detective work, as he calls it, changed how he told the story

in the book, of course.

What a tribute to the attention to detail in today’s best

nonfiction. And to cap it off, Tavares explains

his research process and includes images of the newspapers on his website, so

teachers and librarians can share it with students.

Labels:

baseball,

biographies,

picture-book biographies

Monday, November 18, 2013

The Need for School Librarians

Four out of the five of us were in Connecticut this week for the annual conference of the American Association of School Librarians (AASL) in Hartford. I imagine we all might be posting our ruminations over the next few days. An article posted on Thursday on School Library Journal's website captures the dilemma the city of Hartford and other communities in Connecticut face: a dearth of certified school librarians to provide students with access to books and teachers with the support they need for books and digital texts that can be used in units of study. I heard my own version of this dilemma from a former student teaching in Connecticut.

Just as I was beginning the session that I was moderating, I happened to notice a woman sit down on the end of one of the aisles, a librarian with whom I worked for years in suburban New York City. As a teacher educator speaking to a room full of librarians, it was particularly rewarding to have in that room two librarians from two different public schools in different states in which I've taught. I know I couldn't, and can't, do the work that I do without collaborating with librarians. As districts across the nation try to make the switch to the Common Core Standards, I hope more can look not at the latest "something" that they can buy, but rather, at how they can build capacity within schools by creating and fostering a climate of collaboration between administrators, teachers, literacy coaches, and school librarians.

Just as I was beginning the session that I was moderating, I happened to notice a woman sit down on the end of one of the aisles, a librarian with whom I worked for years in suburban New York City. As a teacher educator speaking to a room full of librarians, it was particularly rewarding to have in that room two librarians from two different public schools in different states in which I've taught. I know I couldn't, and can't, do the work that I do without collaborating with librarians. As districts across the nation try to make the switch to the Common Core Standards, I hope more can look not at the latest "something" that they can buy, but rather, at how they can build capacity within schools by creating and fostering a climate of collaboration between administrators, teachers, literacy coaches, and school librarians.

Friday, November 1, 2013

Exemplary Texts for Thinking About Craft and Structure

A recent article by Karla Moller in the Fall 2013 issue of Journal of Children's Literature entitled "Considering the CCSS Nonfictional Literature Exemplars as Cultural Artifacts: What Do They Represent?" emphasized the need to carefully examine the "exemplary texts" listed in Appendix B. It got me wondering about this famous list. What makes these books exemplary? What are they exemplary of? How do they support learning in content areas and in language and literacy? How do they match curriculum in science, math, and social studies? How do they support learning in these areas?

With these questions in mind, I headed back to Appendix B. I learned--once again--that these books are exemplars of the level of complexity and quality required at different grade bands.

But what if, in addition to having students work so hard to show us they "get" the content, they also focused on the creative part of shaping information? This involves various elements working together--(1) the main idea, (2) the organizational structure, (3) the style of writing, (4) the integration of visual information, and (5) the use of disciplinary thinking. This is the crucial part students often don't get: There is a creative side to writing nonfiction that is influenced by the author's decisions and disciplinary constraints. Even my graduate students are surprised by the flexibility of formats and options open to writers, so I am pretty sure younger students are too. Understanding the process of writing nonfiction is just as important as understanding the content presented.

So I would like to suggest some titles that can be used as exemplars of the craft of shaping information:

The point is this: Even though CCSS has a standard devoted to craft and structure, there is more to it than understanding a collection of separate techniques. The techniques work together in a supportive manner. That's what exemplary text means to me. And, that is why I think this integration of content and craft needs to be further examined.

With these questions in mind, I headed back to Appendix B. I learned--once again--that these books are exemplars of the level of complexity and quality required at different grade bands.

But what if, in addition to having students work so hard to show us they "get" the content, they also focused on the creative part of shaping information? This involves various elements working together--(1) the main idea, (2) the organizational structure, (3) the style of writing, (4) the integration of visual information, and (5) the use of disciplinary thinking. This is the crucial part students often don't get: There is a creative side to writing nonfiction that is influenced by the author's decisions and disciplinary constraints. Even my graduate students are surprised by the flexibility of formats and options open to writers, so I am pretty sure younger students are too. Understanding the process of writing nonfiction is just as important as understanding the content presented.

So I would like to suggest some titles that can be used as exemplars of the craft of shaping information:

- Locomotive by Brian Floca can be read as an example of how poetic language and detailed and sometimes humorous illustration work together to promote understanding.

- Amelia Lost by Candace Fleming can be read to see that there are alternatives to writing biographies in chronological order.

- The Boy on the Wooden Box by Leon Leyson can be read to see how memoir can be written using flashbacks and flashforwards. Once again, an author makes flexible use of chronology to enhance the telling of true story. In this case, the author's open, honest, sincere tone invite us into this compelling story.

- Migrant Mother: How a Photograph Defined the Great Depression by Don Nardo can be read to see how a whole book can be designed to provide context for understanding a single iconic photograph.

- Night Flight by Robert Burleigh and illustrated by Wendell Minor can be read to see how rich, poetic text accompanied by dramatic paintings evoke an event in history.

- What Do You Do With a Tail Like This? by Steve Jenkins and Robin Paige can be read to see how a guessing game with questions and answers can interest readers in thinking about science--in this case, the form and function of animal parts. Jenkins' characteristic cut-paper illustrations support this experience.

The point is this: Even though CCSS has a standard devoted to craft and structure, there is more to it than understanding a collection of separate techniques. The techniques work together in a supportive manner. That's what exemplary text means to me. And, that is why I think this integration of content and craft needs to be further examined.

Friday, October 25, 2013

Testing

A colleague just shared this posting from The Washington Post Answer Sheet blog. Over one hundred authors and illustrators of children's and young adult literature, in cooperation with Fair Test, the National Center for Fair and Open Testing, wrote a letter to President Obama urging him to reconsider the role that standardized tests currently play in public education. I couldn't agree more.

As someone who believes that the Common Core Standards are a flexible continuum for K-12 literacy and content literacy learning, I get discouraged when they are considered synonymous with standardized testing. But for many teachers, particularly those in Race to the Top states, they are synonymous. Teachers are drowning in top down mandates, and have neither the time nor the "permission" to respond to actual student needs and interests. It is possible to be student-centered, creative, and standards-based. But growing readers and writers, and crafting curriculum, instruction, and assessment that is meaningful to children takes time, attention, and a sense of agency that too many teachers no longer have.

There is a clear disconnect between policy makers and educators. There is a clear disconnect between what children need from school and what schools provide for them. There is a clear disconnect about the urgency of the problem, the number of children who are growing completely disengaged with school because it fails to meet their needs as people, as citizens. Clearly, Congress sees no urgency, as it has failed to act on reauthorizing No Child Left Behind, more appropriately known as the Elementary and Secondary Education Act, since it was first up for re-authorization in 2007.

Short of Congressional changes to the law, what can be done? For starters, the Administration can reconsider the role of standardized tests and the emphasis on competition instead of collaboration that runs through the Race to the Top program that it created and continues to promote. Moreover, school leaders, state administrators, and policy makers could provide tools that model authentic assessments, performance-based assessments, and the integration of engaging and age appropriate texts in K-12 classrooms, rather that pouring so much time and money into what PARCC and the Smarter Balanced Assessment consortia are doing.

Parents and engaged citizens can also add their voices of protest. Here is a complete text of the letter, courtesy of the Fair Test website.

October 22, 2013

President Barack Obama

The White House

Washington, DC 20500

Dear President Obama,

We the undersigned children’s book authors and illustrators write to express our concern for our readers, their parents and teachers. We are alarmed at the negative impact of excessive school testing mandates, including your Administration’s own initiatives, on children’s love of reading and literature. Recent policy changes by your Administration have not lowered the stakes. On the contrary, requirements to evaluate teachers based on student test scores impose more standardized exams and crowd out exploration.

We call on you to support authentic performance assessments, not simply computerized versions of multiple-choice exams. We also urge you to reverse the narrowing of curriculum that has resulted from a fixation on high-stakes testing.

Our public school students spend far too much time preparing for reading tests and too little time curling up with books that fire their imaginations. As Michael Morpurgo, author of the Tony Award Winner War Horse, put it, “It's not about testing and reading schemes, but about loving stories and passing on that passion to our children.”

Teachers, parents and students agree with British author Philip Pullman who said, “We are creating a generation that hates reading and feels nothing but hostility for literature.” Students spend time on test practice instead of perusing books. Too many schools devote their library budgets to test-prep materials, depriving students of access to real literature. Without this access, children also lack exposure to our country’s rich cultural range.

This year has seen a growing national wave of protest against testing overuse and abuse. As the authors and illustrators of books for children, we feel a special responsibility to advocate for change. We offer our full support for a national campaign to change the way we assess learning so that schools nurture creativity, exploration, and a love of literature from the first day of school through high school graduation.

Alma Flor Ada

Alma Alexander

Jane Ancona

Maya Angelou

Jonathan Auxier

Kim Baker

Molly Bang

Tracy Barrett

Chris Barton

Ari Berk

Judy Blume

Alfred B. (Fred) Bortz

Lynea Bowdish

Sandra Boynton

Shellie Braeuner

Ethriam Brammer

Louann Mattes Brown

Anne Broyles

Michael Buckley

Janet Buell

Dori Hillestad Butler

Charito Calvachi-Mateyko

Valerie Scho Carey

Rene Colato Lainez

Henry Cole

Ann Cook

Karen Coombs

Robert Cortez

Cynthia Cotten

Bruce Coville

Ann Crews

Donald Crews

Nina Crews

Rebecca Kai Dotlich

Laura Dower

Kathryn Erskine

Jules Feiffer

Jody Feldman

Mary Ann Fraser

Sharlee Glenn

Barbara Renaud Gonzalez

Laurie Gray

Trine M. Grillo

Claudia Harrington

Sue Heavenrich

Linda Oatman High

Anna Grossnickle Hines

Lee Bennett Hopkins

Phillip Hoose

Diane M. Hower

Michelle Houts

Mike Jung

Kathy Walden Kaplan

Amal Karzai

Jane Kelley

Elizabeth Koehler-Pentacoff

Amy Goldman Koss

JoAnn Vergona Krapp

Nina Laden

Sarah Darer Littman

José Antonio López

Mariellen López

Jenny MacKay

Marianne Malone

Ann S. Manheimer

Sally Mavor

Diane Mayr

Marissa Moss

Yesenia Navarrete Hunter

Sally Nemeth

Kim Norman

Geraldo Olivo

Alexis O’Neill

Anne Marie Pace

Amado Peña

Irene Peña

Lynn Plourde

Ellen Prager, PhD

David Rice

Armando Rendon

Joan Rocklin

Judith Robbins Rose

Sergio Ruzzier

Barb Rosenstock

Liz Garton Scanlon

Lisa Schroeder

Sara Shacter

Wendi Silvano

Janni Lee Simner

Sheri Sinykin

Jordan Sonnenblick

Ruth Spiro

Heidi E.Y. Stemple

Whitney Stewart

Shawn K. Stout

Steve Swinburne

Carmen Tafolla

Kim Tomsic

Duncan Tonatiuh

Patricia Thomas

Kristin O'Donnell Tubb

Deborah Underwood

Corina Vacco

Audrey Vernick

Debbie Vilardi

Judy Viorst

K. M. Walton

Wendy Wax

April Halprin Wayland

Carol Weis

Rosemary Wells

Lois Wickstrom

Suzanne Morgan Williams

Kay Winters

Ashley Wolff

Lisa Yee

Karen Romano Young

Jane Yolen

Roxyanne Young

Paul O. Zelinsky

Jennifer Ziegler

CC: Secretary of Education Arne Duncan

For further information, contact:

Monty Neill, Ed.D.

Executive Director

FairTest,

Box 300204

Jamaica Plain, MA 02130

617-477-9792

monty@fairtest.org

As someone who believes that the Common Core Standards are a flexible continuum for K-12 literacy and content literacy learning, I get discouraged when they are considered synonymous with standardized testing. But for many teachers, particularly those in Race to the Top states, they are synonymous. Teachers are drowning in top down mandates, and have neither the time nor the "permission" to respond to actual student needs and interests. It is possible to be student-centered, creative, and standards-based. But growing readers and writers, and crafting curriculum, instruction, and assessment that is meaningful to children takes time, attention, and a sense of agency that too many teachers no longer have.

There is a clear disconnect between policy makers and educators. There is a clear disconnect between what children need from school and what schools provide for them. There is a clear disconnect about the urgency of the problem, the number of children who are growing completely disengaged with school because it fails to meet their needs as people, as citizens. Clearly, Congress sees no urgency, as it has failed to act on reauthorizing No Child Left Behind, more appropriately known as the Elementary and Secondary Education Act, since it was first up for re-authorization in 2007.

Short of Congressional changes to the law, what can be done? For starters, the Administration can reconsider the role of standardized tests and the emphasis on competition instead of collaboration that runs through the Race to the Top program that it created and continues to promote. Moreover, school leaders, state administrators, and policy makers could provide tools that model authentic assessments, performance-based assessments, and the integration of engaging and age appropriate texts in K-12 classrooms, rather that pouring so much time and money into what PARCC and the Smarter Balanced Assessment consortia are doing.

Parents and engaged citizens can also add their voices of protest. Here is a complete text of the letter, courtesy of the Fair Test website.

October 22, 2013

President Barack Obama

The White House

Washington, DC 20500

Dear President Obama,

We the undersigned children’s book authors and illustrators write to express our concern for our readers, their parents and teachers. We are alarmed at the negative impact of excessive school testing mandates, including your Administration’s own initiatives, on children’s love of reading and literature. Recent policy changes by your Administration have not lowered the stakes. On the contrary, requirements to evaluate teachers based on student test scores impose more standardized exams and crowd out exploration.

We call on you to support authentic performance assessments, not simply computerized versions of multiple-choice exams. We also urge you to reverse the narrowing of curriculum that has resulted from a fixation on high-stakes testing.

Our public school students spend far too much time preparing for reading tests and too little time curling up with books that fire their imaginations. As Michael Morpurgo, author of the Tony Award Winner War Horse, put it, “It's not about testing and reading schemes, but about loving stories and passing on that passion to our children.”

Teachers, parents and students agree with British author Philip Pullman who said, “We are creating a generation that hates reading and feels nothing but hostility for literature.” Students spend time on test practice instead of perusing books. Too many schools devote their library budgets to test-prep materials, depriving students of access to real literature. Without this access, children also lack exposure to our country’s rich cultural range.

This year has seen a growing national wave of protest against testing overuse and abuse. As the authors and illustrators of books for children, we feel a special responsibility to advocate for change. We offer our full support for a national campaign to change the way we assess learning so that schools nurture creativity, exploration, and a love of literature from the first day of school through high school graduation.

Alma Flor Ada

Alma Alexander

Jane Ancona

Maya Angelou

Jonathan Auxier

Kim Baker

Molly Bang

Tracy Barrett

Chris Barton

Ari Berk

Judy Blume

Alfred B. (Fred) Bortz

Lynea Bowdish

Sandra Boynton

Shellie Braeuner

Ethriam Brammer

Louann Mattes Brown

Anne Broyles

Michael Buckley

Janet Buell

Dori Hillestad Butler

Charito Calvachi-Mateyko

Valerie Scho Carey

Rene Colato Lainez

Henry Cole

Ann Cook

Karen Coombs

Robert Cortez

Cynthia Cotten

Bruce Coville

Ann Crews

Donald Crews

Nina Crews

Rebecca Kai Dotlich

Laura Dower

Kathryn Erskine

Jules Feiffer

Jody Feldman

Mary Ann Fraser

Sharlee Glenn

Barbara Renaud Gonzalez

Laurie Gray

Trine M. Grillo

Claudia Harrington

Sue Heavenrich

Linda Oatman High

Anna Grossnickle Hines

Lee Bennett Hopkins

Phillip Hoose

Diane M. Hower

Michelle Houts

Mike Jung

Kathy Walden Kaplan

Amal Karzai

Jane Kelley

Elizabeth Koehler-Pentacoff

Amy Goldman Koss

JoAnn Vergona Krapp

Nina Laden

Sarah Darer Littman

José Antonio López

Mariellen López

Jenny MacKay

Marianne Malone

Ann S. Manheimer

Sally Mavor

Diane Mayr

Marissa Moss

Yesenia Navarrete Hunter

Sally Nemeth

Kim Norman

Geraldo Olivo

Alexis O’Neill

Anne Marie Pace

Amado Peña

Irene Peña

Lynn Plourde

Ellen Prager, PhD

David Rice

Armando Rendon

Joan Rocklin

Judith Robbins Rose

Sergio Ruzzier

Barb Rosenstock

Liz Garton Scanlon

Lisa Schroeder

Sara Shacter

Wendi Silvano

Janni Lee Simner

Sheri Sinykin

Jordan Sonnenblick

Ruth Spiro

Heidi E.Y. Stemple

Whitney Stewart

Shawn K. Stout

Steve Swinburne

Carmen Tafolla

Kim Tomsic

Duncan Tonatiuh

Patricia Thomas

Kristin O'Donnell Tubb

Deborah Underwood

Corina Vacco

Audrey Vernick

Debbie Vilardi

Judy Viorst

K. M. Walton

Wendy Wax

April Halprin Wayland

Carol Weis

Rosemary Wells

Lois Wickstrom

Suzanne Morgan Williams

Kay Winters

Ashley Wolff

Lisa Yee

Karen Romano Young

Jane Yolen

Roxyanne Young

Paul O. Zelinsky

Jennifer Ziegler

CC: Secretary of Education Arne Duncan

For further information, contact:

Monty Neill, Ed.D.

Executive Director

FairTest,

Box 300204

Jamaica Plain, MA 02130

617-477-9792

monty@fairtest.org

Monday, October 14, 2013

Wow! It’s Déjà Vu All Over Again

Remember thematic studies? Classroom inquiries? Author

studies? I’m talking about years ago during the Whole Language movement.

Well…the good news is that thematic study is back, but now it has new very

different supporters, which leads me to believe it is a very useful idea

indeed. I almost can’t get over it. Thematic study is something progressive and

conservative educators agree on. It’s a beautiful thing.

Which leads me to my very pragmatic question: What are we

studying? None of the really fine new standards documents—with the exception of

the Next Generation Science Standards— are dealing with content. They are

dealing with process. The new social studies document, for example, The College, Career, and Civic Life (C3)

Framework for Social Studies State Standards: Guidance for Enhancing the Rigor

of the K-12 Civics, Economics, Geography, and History (NCSS, 2013) has an

inquiry arc, but what is being inquired about? Maybe I am still a concrete

thinker, but I am concerned about how all the pieces fit together. And don’t

get me wrong; I think this spanking new document lifts the level of

conversation immensely. Still, I want to see how it works in real life.

So I am proposing a stopgap measure today—some nonfiction

books that I think could jumpstart some inquiries right away.

1.

MALCOLM

LITTLE: THE BOY WHO GREW UP TO BECOME MALCOLM X by Ilyasha Shabazz (Simon

& Schuster, 2013) and MALCOLM X: A

FIRE BURNING BRIGHTLY by Walter Dean Myers (HarperCollins, 2000). These are

two picture books.

First of all, I am not sure that

Malcolm X is a good choice for biography study in the primary grades, since his

transformation as a thinker is quite significant and this is not dealt with in

the first book at all. In spite of this, these two biographies are so vastly

different that they should generate plenty of questions for inquiry. The first

book, written by Malcolm X’s daughter is—as you might expect—a loving tribute

to a father. Yet it leaves out a great deal about his life because (among other

things) it concentrates on his childhood. The second book reveals much more

about the controversial aspects of his life, and that too should generate

questions. What is important to know about Malcolm X? Why?

2.

PLANTING

THE TREES OF KENYA by Claire Nivola (Farrar, 2009), WANGARI’S TREES OF PEACE by Jeanette Winter (Harcourt, 2008), and SEEDS OF CHANGE by Jen Cullerton

Johnson (Lee & Low, 2010) (All titles are picture books.)

These are only some of the books

about the Nobel Prize winner Wangari Maathai, who did so much to plant trees in

Kenya and alert the world to environmental issues However, they tell her story

quite differently. How? What do these various accounts reveal? What do they

leave out? What should people know about Wangari Mathai? Why?

3.

THE BOY

ON THE WOODEN BOX by Leon Leyson (Simon & Schuster, 2013).

This moving memoir by the youngest

survivor on Schindler’s List suggests that Oskar Schindler was a hero because

he did, to quote Joseph Campbell,

“the best of things in the worst of times.” Should we consider him a

hero? What is a hero? Can a person the author describes as “an influential

Nazi” also be a hero?

Of

course, we want children to raise issues for inquiry, but we can also suggest questions

and model the process. Right now the challenge is designing coherent, stimulating,

manageable curriculum that puts the standards to work in our classrooms. The

good news is that literature—fiction and nonfiction—will play a big role.

Wednesday, October 9, 2013

Integration

If ever there was confirmation that the new Common Core Standards are not, in fact, asking that Language Arts and English teachers no longer teach literature, it is the arrival of the new standards for science and social studies. The Next Generation Science Standards, released in April, and the new C3 Framework for College, Career, and Civic Life, released in September, both provide rich opportunities for thinking through evidence, asking and answering meaningful answers, and using experiments, projects, discussions, and a range of other student-centered classroom practices to explore these two disciplines.

Moreover, each is linked to the Common Core State Standards for literacy and content literacy, reaffirming the ways in which teachers, particularly at the elementary level, can integrate instruction to work smarter, go deeper, and fully engage students in inquiry-oriented learning experiences. These standards make it clear that the 50% informational text/nonfiction reading at the elementary level, and the 70% informational/nonfiction reading at the secondary level, can, and should, take place in all content areas across the school year and through the year. Relevant nonfiction reading in the context of the content, what that nonfiction is about, in science and social studies, in addition to relevant reading about craft and structure in the context of student writing in language arts, is the pathway to meeting the expectations of the Common Core and providing students with meaningful explorations of the genre in all of its manifestations.

Principals, curriculum coordinators, literacy coaches, and teams of teachers reading these new standards will see the ways in which integration is made relevant all over again through these standards. As long as curriculum has the opportunity to flourish in schools, rather than skills-as-test-prep in the name of curriculum, students will greatly benefit from these new expectations. There is a lot to learn and a lot to digest, but so many possibilities for capacity-building in school, to create deep, rich curriculum to explore science and social studies and bring in well-written nonfiction trade books and authentic student writing opportunities. I do hope districts, including parents, will push to see this kind of learning taking place in their classrooms.

Moreover, each is linked to the Common Core State Standards for literacy and content literacy, reaffirming the ways in which teachers, particularly at the elementary level, can integrate instruction to work smarter, go deeper, and fully engage students in inquiry-oriented learning experiences. These standards make it clear that the 50% informational text/nonfiction reading at the elementary level, and the 70% informational/nonfiction reading at the secondary level, can, and should, take place in all content areas across the school year and through the year. Relevant nonfiction reading in the context of the content, what that nonfiction is about, in science and social studies, in addition to relevant reading about craft and structure in the context of student writing in language arts, is the pathway to meeting the expectations of the Common Core and providing students with meaningful explorations of the genre in all of its manifestations.

Principals, curriculum coordinators, literacy coaches, and teams of teachers reading these new standards will see the ways in which integration is made relevant all over again through these standards. As long as curriculum has the opportunity to flourish in schools, rather than skills-as-test-prep in the name of curriculum, students will greatly benefit from these new expectations. There is a lot to learn and a lot to digest, but so many possibilities for capacity-building in school, to create deep, rich curriculum to explore science and social studies and bring in well-written nonfiction trade books and authentic student writing opportunities. I do hope districts, including parents, will push to see this kind of learning taking place in their classrooms.

Friday, October 4, 2013

Helping Us Think: Authors Promoting Historical Literacy

When

learning history, a major thematic understanding is time, continuity, and change. As those of us who work with

elementary school aged children know, this understanding doesn’t come easily,

and it does not come automatically. We teachers continuously point out changes

over time, knowing full well that this understanding is slow to develop. Our

students glimpse at the past, fining conditions there “strange and different”

at best, and “weird and stupid” at worst. There is work to be done.

Fortunately,

there are nonfiction books to help us, and it’s important to seek them out and

teach with them. One such book is Kathleen Krull’s Benjamin Franklin (Viking, 2013).

Although there are already many fine books available about Ben Franklin,

this book makes a unique contribution by showing readers how to think about

Franklin in a way that promotes historical literacy.

Krull helps

young readers by sharing her thoughts about history and her unique historical

interpretation. Here are a few examples:

·

Being

explicit about the main idea of the book. In the introduction, she

emphasizes Franklin’s passion for science. She tells us that even though he

accomplished more as a politician, he had a lifetime fascination for science.

According to Krull:

Certainly, a list of Franklin’s

political accomplishments would fill a bigger book. And yet he viewed his

career as a statesman as a leave of absence from his true calling—science.

… Ben Franklin never lost his

excitement about science and injected it into everything he did for

America. (p. 16)

Unlike many other books about

Franklin, this book, a volume in the Giants

of Science series, focuses on Franklin’s scientific accomplishments.

·

Helping

readers understand the historical context. Krull helps readers understand

Franklin as “a man of his times.” When she tells us about conditions that

readers are likely to find strange and even untrue, she underscores this

information and explains it. Here’s what she says about Franklin owning slaves:

She [his wife Deborah] sewed his

clothes, as well as the bindings on the books he printed, and did the

bookkeeping and all the housework until they could afford servants and slaves. Yes,

slaves. For many years, Franklin was a man of his times in accepting slavery,

though unlike some other Founding Fathers he grew to abhor it later in life. (p.

35)

·

Comparing

the something in past to something we know in the present. Krull refers to Franklin’s access to

information as access to an information superhighway. She writes:

Ben Franklin had succeeded in

reinventing himself as something truly cool: the leading source of scientific

information the America, how very own information superhighway. (p. 38)

There’s a lot more to this well-crafted, friendly,

informative book. The style is friendly and interesting. The content is clearly

organized into short chapters dealing with Franklin’s scientific endeavors. The

pen and ink illustrations by Boris Kulikov capture the excitement of Franklin’s

inventions and discoveries.

We often talk about helping kids “read like a writer,” an

idea originally put forth by literacy scholar Frank Smith. To teach history, we

need to read like a historian—thinking

about such things evidence, point of view, and change over time. When authors

share their expertise thinking like a historian and making their thinking

visible, it’s a bonanza for teachers and children.

Friday, September 27, 2013

Fact and Fiction Fused in Play

My daughter Ella is obsessed with birds. Her

favorite birds are tropical, but she is fascinated by all of them. When did

this start? Last January, when her second grade class studied the tropical

rainforest. Ella really wanted to study the Toco Toucan, but another student

did, too, and so Ella formally researched the Capybara (the world’s largest

rodent, for those of you who don’t know) instead. But she didn’t let the

Capybara stop her from learning about the Toco Toucan. In fact, it spurred her

on. Why am I writing about this on a professional blog, you may wonder? Because

what I saw unfold in and out of school last year continues to impact her life

now, and there is a lesson for all of us in the fusion of reading and writing

fiction, nonfiction, and poetry in the context of genuine inquiry and

exploration in the classroom.

Many primary grade teachers have spent the

past ten years focusing almost exclusively on reading, writing, and math skills

because of the statewide assessments demanded by No Child Left Behind. But for

many students, it’s exploring the world, puzzling over maps, studying animals,

and examining artifacts from different cultures and time periods that serve as

the catalyst for reading and writing. This is where the new focus on having

elementary school children read 50% informational text over the course of their

school year is so exciting. Not only will this, hopefully, bring back more

science and social studies instruction in the elementary school so that

students aren’t starting from scratch when they reach middle school, but it

will allow for authentic exploration of nonfiction texts not solely in the

context of language arts and genre study, but in the context of learning

content, of experiencing the world. Learning about the world and reading a

range of nonfiction texts is not boring, it’s liberating. It does not fence off

the imagination, it fuels it.

Ella continues to love learning about birds,

and has enough exposure to fiction, nonfiction, and poetry, that she knows how

to read to learn and write to show what she’s learned. In her spare time, she

reads nonfiction books and websites, observes birds at zoos and in the

backyard, and watches videos and documentaries on endangered birds. She takes

what she has learned about birds and uses the information to write fictional stories

with birds as characters, songs, and nonfiction texts that inform the reader.

Ella continues to love learning about birds,

and has enough exposure to fiction, nonfiction, and poetry, that she knows how

to read to learn and write to show what she’s learned. In her spare time, she

reads nonfiction books and websites, observes birds at zoos and in the

backyard, and watches videos and documentaries on endangered birds. She takes

what she has learned about birds and uses the information to write fictional stories

with birds as characters, songs, and nonfiction texts that inform the reader.

But she has also created a new activity: Birdnastics, where birds experience a

fusion of gymnastics and dance. Her

collection of stuffed birds has grown, and when she comes home from school,

they are often taking classes such as “Seed Splitting and Spitting” or

“Camouflage” at her imaginary school. Fact and fiction are fused in play,

incorporating the best of what she’s learned within her own imaginary world.

Learning about endangered birds and the

endangered rain forest has also fueled Ella’s sense of activism. She wanted to

donate money to the Nature Conservancy on her birthday, and she’s policing our

purchases of chocolate and coffee to ensure that we are buying Fair Trade.

Learning about endangered birds and the

endangered rain forest has also fueled Ella’s sense of activism. She wanted to

donate money to the Nature Conservancy on her birthday, and she’s policing our

purchases of chocolate and coffee to ensure that we are buying Fair Trade.

For Ella, what began in school has spilled

out into her personal life. We have been able to witness how her passion and

curiosity has fueled her learning. There are many children who do not have

access to texts at home, who do not have time and resources to do research as a

personal hobby. For those children, they need school to be the catalyst, to be

the place where fact and fiction are fused in play, where choosing to write fiction or nonfiction about a topic they are exploring is an avenue for agency

and engagement with their learning. They need these wrap-around experiences in

science and social studies to reinforce and extend what they are learning about

language in language arts.

I fear that too many schools are thinking about

the Common Core Standards as simply a checklist of things they have to do,

rather than an opportunity to reorient learning as emancipatory, as a way for

students of all ages to use print and digital texts to interact with the world

beyond school, and perhaps even try to change it.

Tuesday, September 24, 2013

Teens in the Civil Rights Movement

The historic Civil Rights Movement is very much in the news these days, with the anniversary of the March on Washington, the Children’s Crusade March in Birmingham, and more. The next several years will bring other anniversaries of important events to remember and ponder. Fortunately, books for young people offer a rich array of nonfiction on the Civil Rights Movement. Since children and teens played a vital role in the movement, focusing on them is an excellent way to narrow the topic. Middle and high school readers may be more engaged than usual with these history books because the main actors are young people. For young people today who may feel they make little difference in their world, the accounts of teens who did may be a real inspiration.

Two excellent books that introduce

a lot of young people and the dangers they faced to further civil rights are

Cynthia Levinson’s We've Got a Job: The 1963

Birmingham Children's March (Peachtree,

2012) and Elizabeth Partridge’s Marching

for Freedom: Walk Together, Children, and Don't You Grow Weary (Viking, 2009). Students could compare these books for the

Common Core, looking at structure, voice, use of photographs, and more.

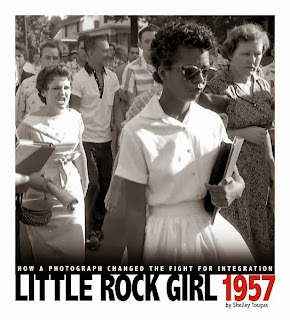

Two

books that give personal views of the integration in 1957 of Little Rock High

are Melba Patillo Beals’ Warriors Don't Cry: A Searing Memoir of the Battle

to Integrate Little Rock's Central High (Pocket, 1995) and Shelley Tougas’s

Little Rock Girl 1957: How a Photograph

Changed the Fight for Integration (Compass Point, 2012). Both concern girls who were among the nine

students to integrate the high school amidst hostility and even violence. The Beals book is a powerful memoir; the

Tougas book is a photo-essay that focuses on a photograph of Elizabeth Eckford,

another of the Nine. They could be used

together, with the Beals’ book suitable for stronger readers and the Tougas

book for those who need shorter texts and more visual support.

Two other excellent texts

highlight teens who made a significant difference. Claudette Colvin: Twice

toward Justice (Melanie Kroupa, 2009) by Phillip Hoose tells of a teenage

girl who not only refused to give up her bus seat in Montgomery before Rosa

Parks but later was one of the plaintiffs when civil rights leaders sued in

federal court to end segregation on the buses.

Because Hoose interviewed multiple times, Colvin’s voice conveys her

difficult, important story.

John Stokes was also part

of a major civil rights lawsuit, Brown v.

Board of Education. He tells his powerful

story, with Lois Wolfe and Herman J. Viola, in Students on

Strike: Jim Crow, Civil Rights, Brown, and Me (National Geographic, 2008). When Stokes was a high school student in

Virginia in the 1950s, he attended an all-black school under the “separate

equal doctrine.” But it was far from

equal to the white school in resources and facilities. He and his fellow students wanted to protest

to get better conditions but ended up, with some reluctance, joining a lawsuit

to integrate the schools. The tough choice brought violent reactions and

shocking retaliation from the county government.

These are all moving stories of great courage, of

kids who put themselves and their families in danger in seeking a better

future, a future with less injustice.

They faced threats, violence, prison cells, police dogs, and more – to make life better future not just for themselves but for those who came after them.

Monday, September 16, 2013

The Education Issue

Last night, I read "The Education Issue" of The New York Times Magazine." Two articles made me think about the role of nonfiction books in K-12 classrooms: "Can Emotional Intelligence Be Taught?" and "No Child Left Untableted." The first article discusses the ways in which some schools are intentionally teaching children how to identify emotions and "reframe" their responses to specific situations. The second discusses the rise of the tablet computer in classrooms and how one county in North Carolina purchased over 15,000 of one particular kind of tablet for its middle school students and teachers.

Now, I happen to think that teaching children and young adults how to navigate their emotional terrain and learn how to work together in community makes sense, particularly when they are bombarded with anger in all forms of their daily life -- from the halls of Congress, to the school cafeteria, to Dance Moms. Kids need help making sense of how the world works, how to read facial cues, how to control their emotions and their voices in heated debates, how to move beyond what they think someone meant in order to actually have a dialogue about what they did. If teachers don't help students do that, some will never learn. And to pretend that conflict doesn't exist within a classroom or outside in the halls makes no sense. Everyone suffers. Kids need tools and strategies. But do I think you need to buy an expensive program to do this? No. Certainly, I'm biased, but in my work with middle and high school students over the years, we learned to have those conversations in the context of exploring literature and history, through the voices of the present and the past. Having sustained discussion, creating a classroom context in which students can safely talk about texts but also talk about themselves, their world, their conflicts, matters. Not just in order to develop the speaking and listening skills they need or to cite evidence from the text to demonstrate critical thinking, but because it helps them to develop empathy and understanding of lives beyond their own. Nonfiction books can help students and teachers have those conversations, can bring the world into the classroom and the classroom out into the world. Teachers need to be know about those trade books, have the ability to choose the trade books best able to to meet the needs and interests of their particular community, and have the funds to purchase them. Most schools don't have that money. Or, it is not permitted to spend it on something as "risky" as trade books.

Guilford County, North Carolina has a lot of money to spend, thanks to Race to the Top. The author of the second article writes, "The tablets, paid for in part by a $30 million grant from the federal

Department of Education’s Race to the Top program, were created and sold

by a company called Amplify, a New York-based division of Rupert

Murdoch’s News Corporation, and they struck me as exemplifying several

dubious American habits now ascendant: the overvaluing of technology and

the undervaluing of people; the displacement of face-to-face

interaction by virtual connection; the recasting of citizenship and

inner life as a commodified data profile; the tendency to turn to the

market to address social problems." As I read the second article, I wondered what kinds of discussions might not take place in Guilford County, North Carolina this year because of the pressure teachers must feel to maximize their use of the tablet computers.

I do not believe in a false dichotomy between print and digital texts. I think that as educators, we need to use all types of texts and genres with students to explore the world. Students need to be reading and writing multigenre and multimodal texts as well as traditional text types. But when one company is deciding the reading material for thousands of children, and a school district abdicates that responsibility, I am afraid. Why does it seem okay to take those decisions away from the teachers and librarians who know children best? I love tablet computers for their portability of content, for the ways in which students can construct texts. I couldn't teach without the range of digital resources my university's library provides through its databases. But I am the one who decides what my students read. And when I taught middle and high school, I was the one who decided what my students read. Or they decided.

Tuesday, September 10, 2013

Adaptations of Adult Nonfiction Books

Back in the 1980s when I became a children's librarian, I had a negative perception of books written for adults that had then been adapted for children. I can't remember any actual titles but I recall thinking they were probably all hatchet jobs. I'm happy to say that's no longer the case. A number of fine adaptations of nonfiction have been published in the past few decades, mostly aimed at middle schoolers.

This morning I compiled a Pinterest Board that I called, in my usual imaginative way, "YA Nonfiction Books Adapted from Adult Nonfiction." (http://pinterest.com/kodean/ya-nonfiction-books-adapted-from-adult-nonfiction/) Right now it has 15 books that I've read and enjoyed, plus a Spanish version of a book I read in English. In only one case have I read both the adult and the teen version: Mayflower and The Mayflower and the Pilgrims' New World, both by Nathaniel Philbrick and both excellent.

Many of the books made it onto bestseller lists in their adult version, typically ones on historical subjects like James Bradley's Flags of Our Fathers, which kept the same title for young people, and James L. Swanson's Manhunt, published for young people as Chasing Lincoln's Killer.

Most of the books on my Pinterest board were published in the 2000s, but two of my favorites came out in the 1990s. I often recommend Warriors Don't Cry: A Searing Memoir of the Battle to Integrate Little Rock's Central High by Melba Pattillo Beals for teen book clubs or classrooms. Beals was one of the Little Rock Nine who helped change the world in 1957, and her story never feels old or less moving.

Nor has Michael Collins' story in Flying to the Moon, based in part on his Carrying the Fire, lost its drama. He describes being the astronaut who piloted the command module while Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin took the first moon walk. He was the first person alone on the dark side of the moon. Like Beals, he's a fine writer with a gripping tale to tell.

Two recent adaptations speak to the lives of very different young Hispanic men. In They Call Me a Hero: A Memoir of My Youth (available in Spanish as well as English), Daniel Hernandez recounts his role in helping save Representative Gabby Giffords's life in 2011. Of Mexican descent, Hernandez writes about his upbringing and his determination to succeed, discounting his label as a "hero" and focusing on what matters most to him.

Enrique's Journey: The True Story of a Boy Determined to Reunite with His Mother by Sonia Nazario, based on her adult book and Pulitzer Prize winning L.A. Times articles, is the devastating account of a Honduran teenager who rides on train tops through Guatemala and Mexico trying to reach his mother in the U.S. Time and time again, he's sent back to Honduras or Guatemala by immigration police. More than once he's robbed and beaten by gangs. He finally reunites with his mother, who's struggling as an illegal immigrant, but it's far from the fairy tale ending Enrique had hoped for.

Many of the adult nonfiction on my Pinterest board presumably sells mostly to men or as gifts for men, and may especially appeal to your male students. If you do a Read Across the School book in high school, consider using both versions of one of these books, offering stronger readers and adults the more challenging one. The two versions overlap enough to provide plenty to discuss. Warriors Don't Cry, They Call Me a Hero, and Enrique's Journey focus on young people and offer a lot that students can relate to.

Make a display of adapted nonfiction books, add them to summer reading lists, and make sure students and teachers know how good they are. And read a few yourself, if you haven't already, to see how much adaptations have changed.

This morning I compiled a Pinterest Board that I called, in my usual imaginative way, "YA Nonfiction Books Adapted from Adult Nonfiction." (http://pinterest.com/kodean/ya-nonfiction-books-adapted-from-adult-nonfiction/) Right now it has 15 books that I've read and enjoyed, plus a Spanish version of a book I read in English. In only one case have I read both the adult and the teen version: Mayflower and The Mayflower and the Pilgrims' New World, both by Nathaniel Philbrick and both excellent.

Many of the books made it onto bestseller lists in their adult version, typically ones on historical subjects like James Bradley's Flags of Our Fathers, which kept the same title for young people, and James L. Swanson's Manhunt, published for young people as Chasing Lincoln's Killer.

Most of the books on my Pinterest board were published in the 2000s, but two of my favorites came out in the 1990s. I often recommend Warriors Don't Cry: A Searing Memoir of the Battle to Integrate Little Rock's Central High by Melba Pattillo Beals for teen book clubs or classrooms. Beals was one of the Little Rock Nine who helped change the world in 1957, and her story never feels old or less moving.

Nor has Michael Collins' story in Flying to the Moon, based in part on his Carrying the Fire, lost its drama. He describes being the astronaut who piloted the command module while Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin took the first moon walk. He was the first person alone on the dark side of the moon. Like Beals, he's a fine writer with a gripping tale to tell.

Two recent adaptations speak to the lives of very different young Hispanic men. In They Call Me a Hero: A Memoir of My Youth (available in Spanish as well as English), Daniel Hernandez recounts his role in helping save Representative Gabby Giffords's life in 2011. Of Mexican descent, Hernandez writes about his upbringing and his determination to succeed, discounting his label as a "hero" and focusing on what matters most to him.

Enrique's Journey: The True Story of a Boy Determined to Reunite with His Mother by Sonia Nazario, based on her adult book and Pulitzer Prize winning L.A. Times articles, is the devastating account of a Honduran teenager who rides on train tops through Guatemala and Mexico trying to reach his mother in the U.S. Time and time again, he's sent back to Honduras or Guatemala by immigration police. More than once he's robbed and beaten by gangs. He finally reunites with his mother, who's struggling as an illegal immigrant, but it's far from the fairy tale ending Enrique had hoped for.

Many of the adult nonfiction on my Pinterest board presumably sells mostly to men or as gifts for men, and may especially appeal to your male students. If you do a Read Across the School book in high school, consider using both versions of one of these books, offering stronger readers and adults the more challenging one. The two versions overlap enough to provide plenty to discuss. Warriors Don't Cry, They Call Me a Hero, and Enrique's Journey focus on young people and offer a lot that students can relate to.

Make a display of adapted nonfiction books, add them to summer reading lists, and make sure students and teachers know how good they are. And read a few yourself, if you haven't already, to see how much adaptations have changed.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)